Action Network senior writer Collin Wilson has been sharing what a 12-team playoff would look like each week in the wake of the CFP committee’s rankings. Two things stand out to me right away.

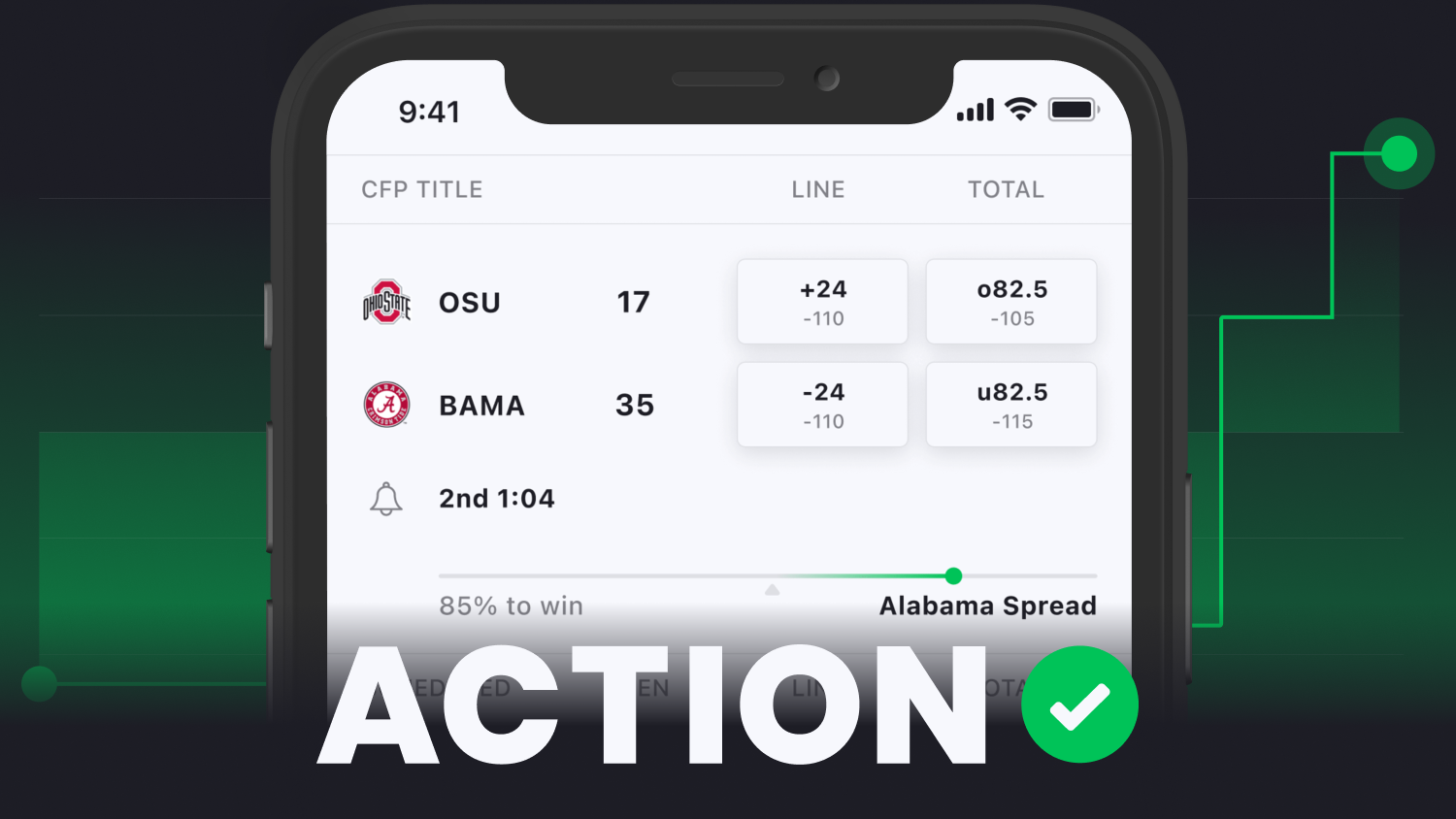

The first is that every single first-round matchup is projected to be outside of 10 points from a point spread perspective:

- Florida State -13.5 vs. Tulane

- Oregon -10.5 vs. Penn State

- Texas -10.5 vs. Louisville

- Alabama -12 vs. Missouri

And the second is that our sport’s regular season has already done a thorough job of vetting these teams — or at least will in the next two weeks.

Case in point, Ohio State and Michigan will meet on Saturday to settle the Big Ten East. Barring a sizable upset in Oregon State vs. Oregon, the Ducks and Washington are set to face off in the Pac-12 title game in two weeks. And finally, Georgia and Alabama are on a collision course for the SEC crown.

Would a larger field create interesting first-round matchups on an annual basis? Absolutely — particularly for teams like Tulane and Louisville, who haven’t had the opportunity to fully strut their stuff this season due to scheduling limitations.

But have we really blown up the entire sport so that a 10-1 AAC team can get fed into the woodchipper? Did we do it to provide a Louisville team that lost by 17 to a moribund Pitt team on the road a path to the national title? And if so, why?

And that’s not even mentioning teams like Penn State and Ole Miss, who are right on the cut line and have been convincingly beaten when given opportunities to break through this season against elite opponents.

All this expanded playoff is going to do is make it less likely that we get the best two teams on the field, at optimal health, by the end of the season. This isn’t the PGA Tour — playing more frequently takes a toll and can turn the sport into a battle of attrition.

We saw it last weekend with the injury to Florida State's Jordan Travis, and we’ve seen it impact College Football Playoff games in recent years as well.

Expanded postseasons are made-for-TV spectacles that can deliver more exciting outcomes but come at the expense of identifying the sport’s best team.

We’ve already seen this play out on the diamond.

The playoff expansion creep hit America’s pastime slowly at first and then at an accelerated pace. Beginning in 1969, two teams from each league would face off in the postseason for a chance to play in the World Series. Just four of the 24 teams (16.6%) qualified that first year, and the percentage of playoff teams decreased as MLB expanded to 28 teams by 1993.

The result of these limited postseason slots was that the participants oftentimes were of the highest quality. Major League Baseball utilized this format for 25 years, and if you remove team data from the strike-shortened 1981 season, a few things stand out.

Teams that made the World Series averaged 97 regular-season wins, and 62.5% of World Series champions won 95-plus games. In those 24 Fall Classics, only one champion had fewer than 90 wins — the 1987 Minnesota Twins.

But then MLB decided to expand its postseason.

First, in 1995, they doubled the size of the postseason field from four to eight, while introducing the Wild Card in addition to divisional playoff bids. World Series champions with 95-plus regular season wins fell from 62.5% in the old format to 41.2% in the new postseason bracket.

And while we saw just one champion with fewer than 90 wins from 1969-93, two teams accomplished the feat in the next 12 years with the Yankees in 2000 and Cardinals in 2006.

In 2012, MLB added two more teams to the field, and once more in 2022, settling on six teams in each league for a total of 12 postseason berths.

What started as a postseason that included 16.6% of all teams in 1969, had ballooned to 40% by 2022. In the past five World Series, removing the COVID-19 season, at least one team with 93 regular-season wins or fewer has qualified for the Fall Classic.

The result of the expanded playoff is that lower-quality teams are competing on the World Series stage and the top teams are no longer meeting at all. In fact, the last time the top team from the AL met the top team from the NL was 10 years ago when the Red Sox faced the Cardinals.

Action Network’s Anthony Dabbundo covers MLB throughout the year and had this to say about its postseason:

“The MLB postseason has never been a great way of truly determining who the best MLB team was in a given season due to the high variance nature of the sport. They play 162 games in a true marathon for almost six months, and then even a near-100 win team like the Rays in 2023 can be knocked out in two games. Or the Atlanta Braves, who had MLB's best record, get knocked out in four games in the NLDS, MLB's equivalent of the quarterfinals.

“The more teams you allow into the playoffs, the more likely you are to get upsets and variance, like the 6-seed Phillies winning the NL in 2022 or the 6-seed Diamondbacks winning the NL in 2023. Studies have shown you'd need to play best-of-75 series for the better team to win 80% of the time.

We choose this format over the European soccer model because of playoff excitement, even though the European soccer model is far better at crowning the best team over a whole season with a double round-robin balanced schedule and no playoffs. It's why Leicester City's EPL title win in 2015-16 will always be the greatest upset in modern sports history for me. They didn't just need to be great for a game or a month but had to pull it off for an entire season.”

College basketball has gone through a similar expansion explosion.

By the early 1970s, the NCAA had crafted a series of rules to ensure that its tournament, and not the NIT, would be viewed as the preeminent postseason event. The winner of the NCAA Tournament would be crowned as the national champion.

By 1975, the Big Dance began to resemble what we know today. It included major conference champions and at-large bids, inviting 32 teams in total.

In that first season, the Final Four included UCLA, Louisville, Syracuse and Kentucky. Three of those four teams entered the tournament in AP Poll's top six. The event matched the best vs. the best.

But soon, TV executives and conference commissioners began to exert some pressure on the NCAA.

By 1980, the NCAA was feeling the pressure to expand. It added eight teams to the field in 1980 and another 12 in 1983 before finally landing on 64 teams in 1985. A full doubling of the field in just a decade.

Unlike that first Final Four in 1975, the national semifinal had become a destination for unlikely challengers. Starting with Villanova in 1985 and running through the first four years of the 64-team field, the Final Four included a team ranked outside the AP Top 25 in the final pre-tournament rankings.

There's so much to like about the NCAA Tournament, namely the first weekend which provides small schools with an opportunity to capture program-defining upsets. The tournament and brackets that go along with it are a cultural touchstone that unites casual fans, diehards, analytics junkies and ardent gamblers alike.

But in terms of the tournament being a fair vehicle geared toward identifying the best team, it’s far from perfect.

In a sport that's subject to wild 3-point variance, a team like UMBC can use a 50% shooting night from 3-point range to upset a No. 1 seed by 20 points, as the Retrievers did in 2018.

Flukey outcomes are the reason that professional leagues opt for five- and seven-game series on the hardwood instead of the do-or-die single-elimination format.

But what’s lost in the upsets and excitement is that your path can matter just as much as your personnel. By including 68 teams in college basketball and 12 teams in college football, there will always be a chance that upsets create pseudo-red carpets for teams.

For example, take Florida Atlantic — a March Madness Cinderella last spring that earned an automatic bid and a 9-seed in the NCAA Tournament as the Conference USA champion.

Because of Fairleigh Dickinson’s upset of Purdue, it avoided playing one of the nation’s top teams in the second round. Its run was aided by the fact that it didn’t face a single team ranked inside the AP Top 14. Yet, had the Owls won, they would have unquestionably been viewed as the national champion.

In college football, upsets and injuries will play a similar role. By adding one to two additional games, we’ll have the opportunity for teams to play spoiler and for star players to be sidelined.

Star offensive players like Jameson Williams and Marvin Harrison Jr. both missed time in College Football Playoff games in recent years. Without Williams, an Alabama runaway in the SEC title game turned into a double-digit defeat in a national title game rematch.

Meanwhile, Harrison was knocked out of last season’s Peach Bowl late in the third quarter with Ohio State leading by 14 points. Without Harrison, they would blow the lead and lose by one.

This isn’t a debate over what would have happened had Williams and Harrison been able to start and play four quarters against Georgia in the past two playoffs. This is simply an illustration that more games have the potential to take the best players off the field, and upsets have the potential to create roads for certain teams.

For example, in the hypothetical listed above. Georgia could face Mizzou and the winner of Tulane vs. Florida State (with a backup quarterback) to reach the National Championship. At the same time, a team like Washington, through no fault of its own, could be forced to beat Oregon and Ohio State just for the right to play in the national title game.

In a sport that already deals with scheduling issues at its core, at least the four-team playoff was delivering fairly comparable difficulty in each semifinal on an annual basis. That could very well go out the window in Year 1 of the expanded playoff.

Power brokers in and around the sport killed off the importance of the Rose Bowl, marginalized the regular season and tripled the size of the postseason field so that teams in the 8-20 slots of the College Football Playoff rankings could have something to play for in November.

Is that the rational?

Because if they contend that the reason for all of this upheaval is that there's a true national champion lurking in the 9-16 slots of the rankings at this point in the season, I officially cannot hold my tongue any longer.

The playoff expansionist movement has repeatedly claimed that no one can evaluate these teams unless they meet on the field, despite a tsunami of advanced analytics in recent years and the fact that many of these teams do play during the course of the season already.

To sit here and insist that we need to have a larger field to determine if Penn State is actually the best team is not only disingenuous, but it’s going to harm the entire process.

We will get some fun first-round matchups, particularly with energized Group of Five teams playing the role of Cinderella. But let’s at least admit, as a sport, that this is a flawed way to determine a champion.

So, brace for the injuries, a two- or perhaps three-loss national champion and waking up college football casuals only once the postseason rolls around, as has become custom in college basketball.

This will be the new normal.