Anybody who has been watching the NHL for more than a few seasons knows that the game has changed. Scoring is up, save percentages are down, and power play percentages are as high as they've been in 40 years. There's really no arguing that the league is more skilled now than it ever was, and yet, ratings and interest seem to be trending in the wrong direction.

At the All-Star break, Austin Karp of the Sports Business Journal reported that NHL U.S. TV national viewership is down 22% this season and that, to that point, games on ESPN/TNT averaged 373,000 viewers compared to 478,000 in 2021-22.

There are plenty of salient arguments to be made as to why ratings and interest seem down in a year when scoring and comebacks are soaring, but perhaps the one that nobody wants to admit is the driving force behind all of this is that tanking has become endemic in the National Hockey League.

Over the past few seasons, the NHL has been a competition of "haves and have-nots." In other words, half the teams in the circuit seem to be actively trying to win, while the other half is tanking. And the gap between the camps is as wide as it's ever been.

This problem is not unique to the NHL, of course. We've normalized tanking across every major North American sport, but tanking to this extreme is a new phenomenon in hockey.

That's a problem for a league that prides itself on parity and an ethos of "anybody can beat anybody on any given night."

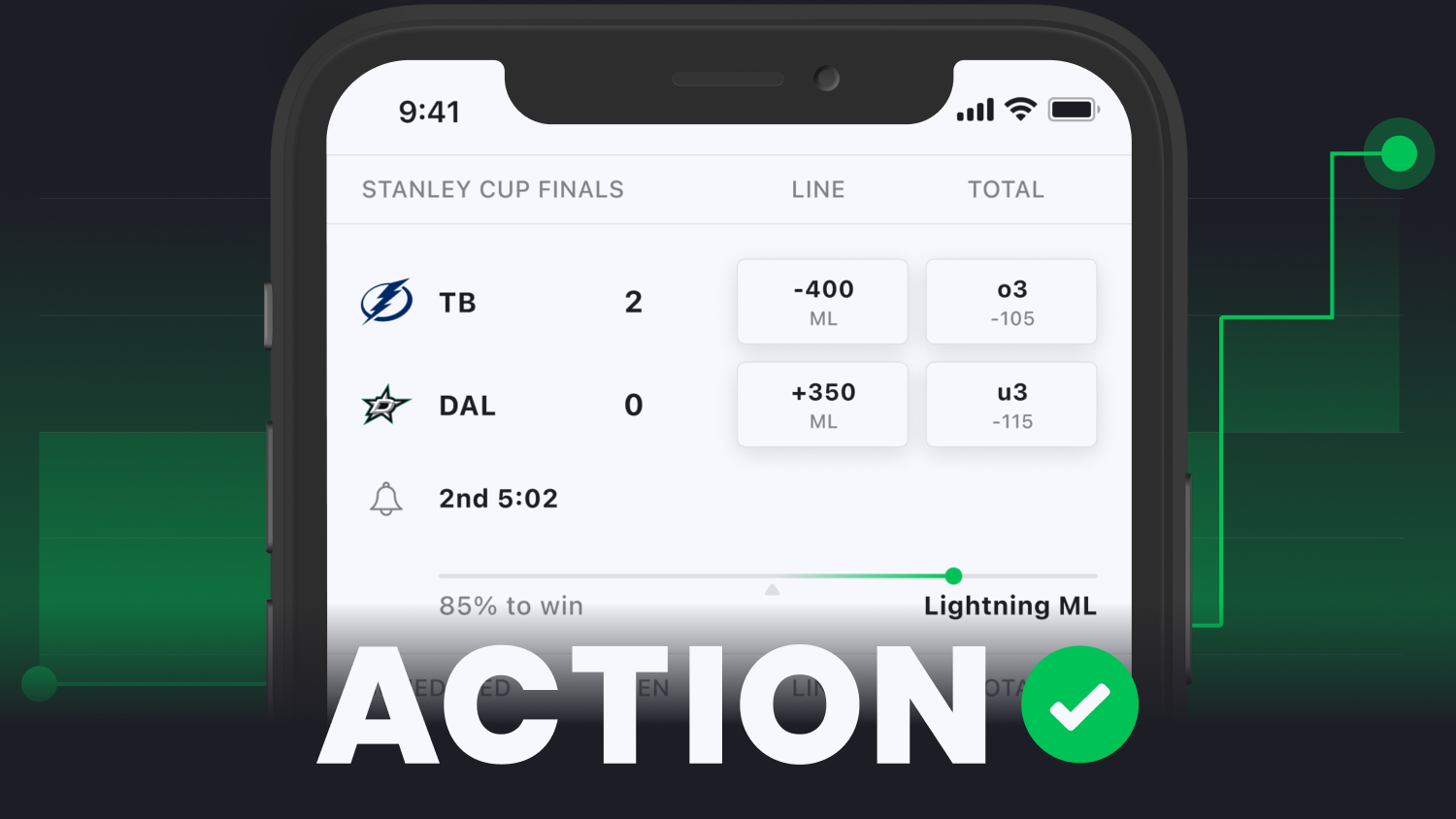

Perhaps the best way to illuminate this issue is with, of all things, the betting market.

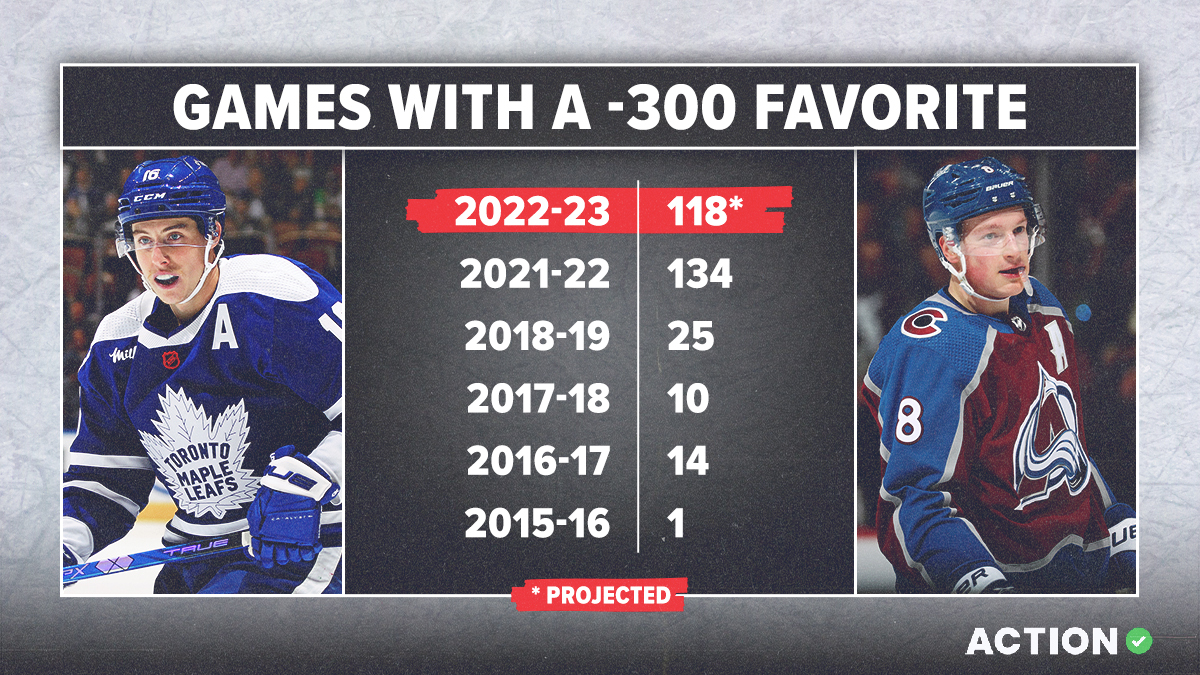

According to Action Labs, there have been 596 NHL games since 2005-06 that featured a team that closed at -300 or higher. That averages out to about 33 per season, or 2.5% of all NHL games that have taken place since the league came back from the 2004-05 lockout.

Why did I choose -300 as the benchmark? Because a team that closes at -300 has an implied win probability of right around 75%. In other words, if you're betting on a team that's -300 to win a game, it's because you think they win that game more than 75% of the time. That seems like a fair benchmark to call a game a "mismatch."

For a long time, the NHL had very few "mismatches." From 2005-06 to 2019-20, there were 338 games with a favorite of at least -300. That averages out to about 1.9% of contests, or around 23 games per campaign.

In that timeframe, the most "mismatches" in a single season was 2005-06 with 78. The following season had 71. The next two had seven each.

The next decade saw the number of "mismatches" tick up from what we saw from 2007-09, but it was nothing like we're seeing in the post-pandemic era. In 2019-20, there were 17 games that featured a favorite of -300 or higher. In 2018-19 there were 25. The average number of games that featured a -300 favorite or longer in the seven seasons from 2013-14 to 2019-20 was 17.

The shortened, division-only 2020-21 season had 43 "mismatches" out of 868 total games (5%), but that year was an anomaly. Teams played almost exclusively in empty buildings and played games only within their divisions.

But the following season saw a seismic shift in competitive balance. The 2021-22 season was the first year for the Seattle Kraken, meaning there were 32 teams playing a 1,312-game schedule. Of those games, there were a whopping 134 "mismatches." That's more than 10%. In other words, if there was an NHL slate with 10 games on it, the chances were that one of those games would feature a team with NHL odds of at least -300.

And that's not the only issue with how things are trending. If there are so many games that feature huge favorites because there are a lot of bad teams, it also means you're going to have a lot of meaningless games between bad teams. From November to April in 2021-22, there were 970 total games played in the NHL, and 184 of them were played between two squads with a sub-50% win rate. That's roughly 19%.

In other words, on a night in which there were 10 NHL games, you'd likely have at least one mismatch and then two "meaningless" tilts between bad teams. And with the way the NHL sets up its nightly schedule, which is usually heavy on 7 p.m. ET starts and then a slew of 9:30 or 10 p.m. ET puck-drops, it means you could have a night when an entire timeslot is filled with terrible games.

That's not how you grow the game, but at the same time, it's hard to blame these franchises for going this route. The system is broken and hockey clubs are doing their best to succeed within it.

This spring, one team will win the right to draft generational talent Connor Bedard and change the fortunes of its franchise. The teams that miss on Bedard will also get terrific prospects in what is considered the deepest draft since 2015. But the tank-a-thon becoming a normalized-bordering-on-celebrated phenomenon is not a good thing for the health of the game, and it's showing this season, which once again is on pace to set records for offense and comebacks.

The 2022-23 NHL season will feature 1,312 games, but we've already played 898. Of those 898, we've had 81 games that featured a favorite of at least -300. That's about 9% of all games. If we pro-rate that out, we'll land on about 118 games this season with a team that closed at least -300. And it'll likely be more than that since bad teams will get worse at the deadline and trade their good players to the better teams. The gap only widens as the season goes on.

But, let's stay conservative and say that we land on 118 "mismatches." That would mean over just the past two seasons, we'll have witnessed 252 NHL games with a favorite of at least -300. From 2005-06 to 2020-21, we had a total of 381.

Over the last 20 years, the party line was that an increase in scoring would lead to an increase in ratings, interest and all that comes with it for the NHL. But in a season when offense is running rampant, ratings are down and interest seems muted at best.

Maybe it's because of the competition for eyeballs. Maybe it's part of a societal shift from the pandemic. Maybe it's the cord-cutting revolution.

But perhaps it's something else entirely. The idea of tanking and setting a team up to purposefully fail has been normalized in the sports universe. A lot of oxygen is spent on "whether Team A should tear it down and rebuild," and plenty of ink is spilled criticizing teams for trying to win games and not giving up on a season.

For a long time, it looked like the NHL was the outlier in this whole ordeal. The league had plenty of flaws, but for the most part, most clubs (with a few exceptions, of course) tried to win games, rather than lose on purpose to get the best odds in a draft lottery.

That has changed. And it sucks.