Fanatics became the first licensed sportsbook in the U.S. to launch a prediction market, going live with Crypto.com powering its backend infrastructure. It has major sports available, player outcomes (like anytime touchdowns and passing yards) for NFL games, plus some political and economic markets.

Fanatics Markets isn't available in all states (mostly ones without Fanatics Sportsbook).

So what can you expect when you use Fanatics Markets, and how does it differ from their sportsbook product? Let's dive in.

Where Can I Use Fanatics Markets?

Fanatics Markets launched Wednesday in Alaska, Delaware, Hawaii, Idaho, Maine, New Hampshire, North Dakota, Rhode Island, South Dakota, and Utah, followed by Alabama, Minnesota, Mississippi, Nebraska, New Mexico, Oklahoma, Oregon, South Carolina, and Wisconsin on Thursday, then California, Florida, Georgia, Texas, and Washington on Friday.

At a high level, how does Fanatics Markets Work?

Fanatics Markets, like its prediction market competitors, is a "peer to peer" network in which you're trading against another party, not the house, like you would at a sportsbook. Though the other party could be a regular retail bettor, a market maker, a big company offloading risk, or a sophisticated institutional investor.

The interface should feel familiar — you click a side you like, the selection pops up in a slip, and you can enter your dollar amount. But the main difference is that you're trading "contracts" that, when settled, will all add up to $1. You can also view the contract amounts as probabilities.

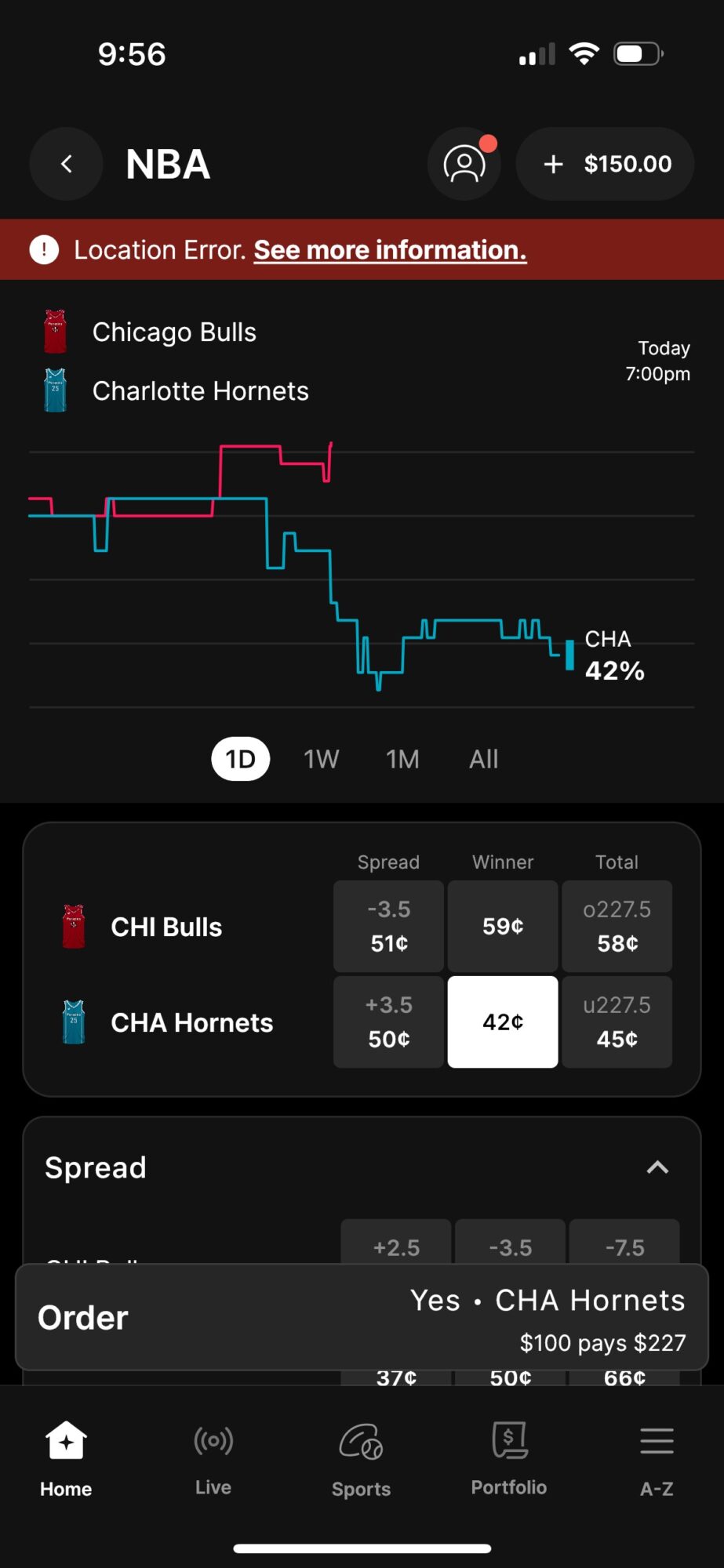

Take this example: I want to take the Hornets at 42 cents to beat the Bulls, which means the market gives the Hornets about a 42% chance to win.

- I buy each contract for 42 cents

- If it wins, I get $1 for each contract — my 42 cents back, plus 58 cents profit.

- That equates to about +136 in American odds (though I'll give some of that profit back in fees, so it's really more like +128).

The contracts all work like this, settling as either "yes" or "no" for $1 each. It's a bit of a mindset shift for people used to sports betting.

Are there fees?

Unlike a traditional sportsbook, where the "fees" are sort of baked into the prices via the juice, prediction markets charge fees on the trades themselves. That's why if you trade a 50-cent contract for $10, you won't profit $10 — it'll be more like $9 and change.

The fees depend on the trade price. For most trades, you'll end up paying about 2% (2 cents per $1). Here's a rough example of what you can expect to pay (the full fee schedule is here).

What is an orderbook, and how do the prices move?

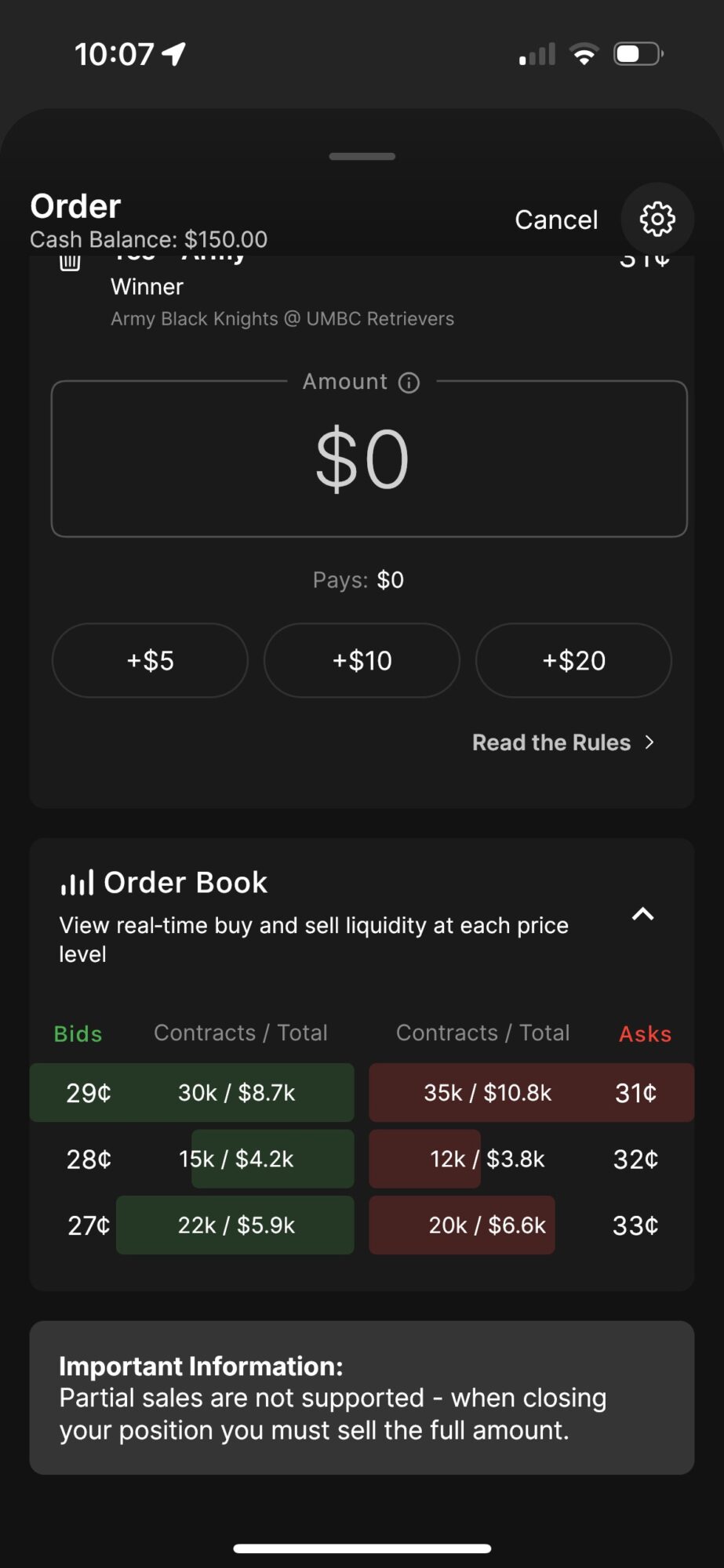

An orderbook is how you view real-time liquidity for each price. Most normal users won't be interested in this on a trade-to-trade basis, but it's worth understanding as you use the platform.

It's like trading a stock. There needs to be another party selling the stock so that you can buy it. So market makers on prediction markets put in "orders" that they're comfortable selling at.

One group may be comfortable selling Army basketball at 31 cents, another at 32 cents.

Take the example below:

- There's $10,800 of liquidity available for Army to beat UMBC in college basketball at 31 cents.

- If I came in and took all that liquidity with a $10,800 purchase at 31 cents, the market would move to the next price, which is 32 cents.

- Of course, traders can remove liquidity from the pool whenever they want, or add new liquidity at different prices.

The prices could move on injury news, but more likely, it's tied to the broader sports betting market — if there's a huge move at a market-making sportsbook, the parties offering the liquidity will likely move their prices to reflect it.

Why don't the percentages add up to 100%?

The difference between the "yes" and "no" sides of a given trade is called the spread.

It's the gap between what the highest price a buyer will pay (bid) and the lowest price a seller will accept (ask). A narrow spread indicates high demand, while a wide spread indicates low demand. Market-makers make money by buying at a lower price and then selling at a higher price.

The bigger the gap between the "yes" and "no" means the market is less confident in the price. In a super-liquid market with lots of action, like most sporting events, the two sides should be pretty close to 100%. In a market with much more uncertainty (like who will be the next coach at Michigan), the percentages will add up to more than 100%.